Ken’s Artisan Pizza - Portland, OR

We should treat laws passed by Congress the way we treat pills prescribed by doctors. Each bill should come with a section of potential side effects.

“This regulation may cause…”

What goes on the law’s warning label should also be debated, pros and cons included. Lawmakers can attach their names to the various side effects. The more accurate each lawmaker’s predictions are over time, the higher their side effect claims live on the list.

“One of the first interesting experiences I had in this project at Princeton was meeting great men. I had never met very many great men before. But there was an evaluation committee that had to try to help us along, and help us ultimately decide which way we were going to separate the uranium.

This committee had men like Compton and Tolman and Smyth and Urey and Rabi and Oppenheimer on it. I would sit in because I understood the theory of how our process of separating isotopes worked, and so they’d ask me questions and talk about it.

In these discussions one man would make a point. Then Compton, for example, would explain a different point of view. He would say it should be this way, and he was perfectly right. Another guy would say, well, maybe there’s this other possibility we have to consider against it.

So everybody is disagreeing, all around the table. I am surprised and disturbed that Compton doesn’t repeat and emphasize his point. Finally, at the end, Tolman, who’s the chairman, would say, “Well, having heard all these arguments, I guess it’s true that Compton’s argument is the best of all, and now we have to go ahead.”

It was such a shock to me to see that a committee of men could present a whole lot of ideas, each one thinking of a new facet, while remembering what the other fella said, so that, at the end, the decision is made as to which idea was the best - summing it all up - without having to say it three times. These were very great men indeed.”

- Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

I’ve written before about how enthusiasm is my favorite quality in others. It’s what pulls me closer to people.

Here, a student describes Richard Feynman’s enthusiasm:

I remember when I was his student how it was when you walked into one of his lectures. He would be standing in front of the hall smiling at us all as we came in, his fingers tapping out a complicated rhythm on the black top of the demonstration bench that crossed the front of the lecture hall. As latecomers took their seats, he picked up the chalk and began spinning it rapidly through his fingers in a manner of a professional gambler playing with a poker chip, still smiling happily as if at some secret joke. And then - still smiling - he talked to us about physics, his diagrams and equations helping us to share his understanding. It was no secret joke that brought that smile and the sparkle in his eye, it was physics. The joy of physics! The joy was contagious. We are fortunate who caught that infection.” -from the foreward of Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

Here are two surprising facts: the number of people who have moved across state lines is down 51% since the mid-20th century; the number of business owners under the age of 30 is down 65% since the 1980’s.1

Watch the news and you’d get a different impression. Why is dynamism falling?

I’ve added Tyler Cowen’s book to my Goodreads list.

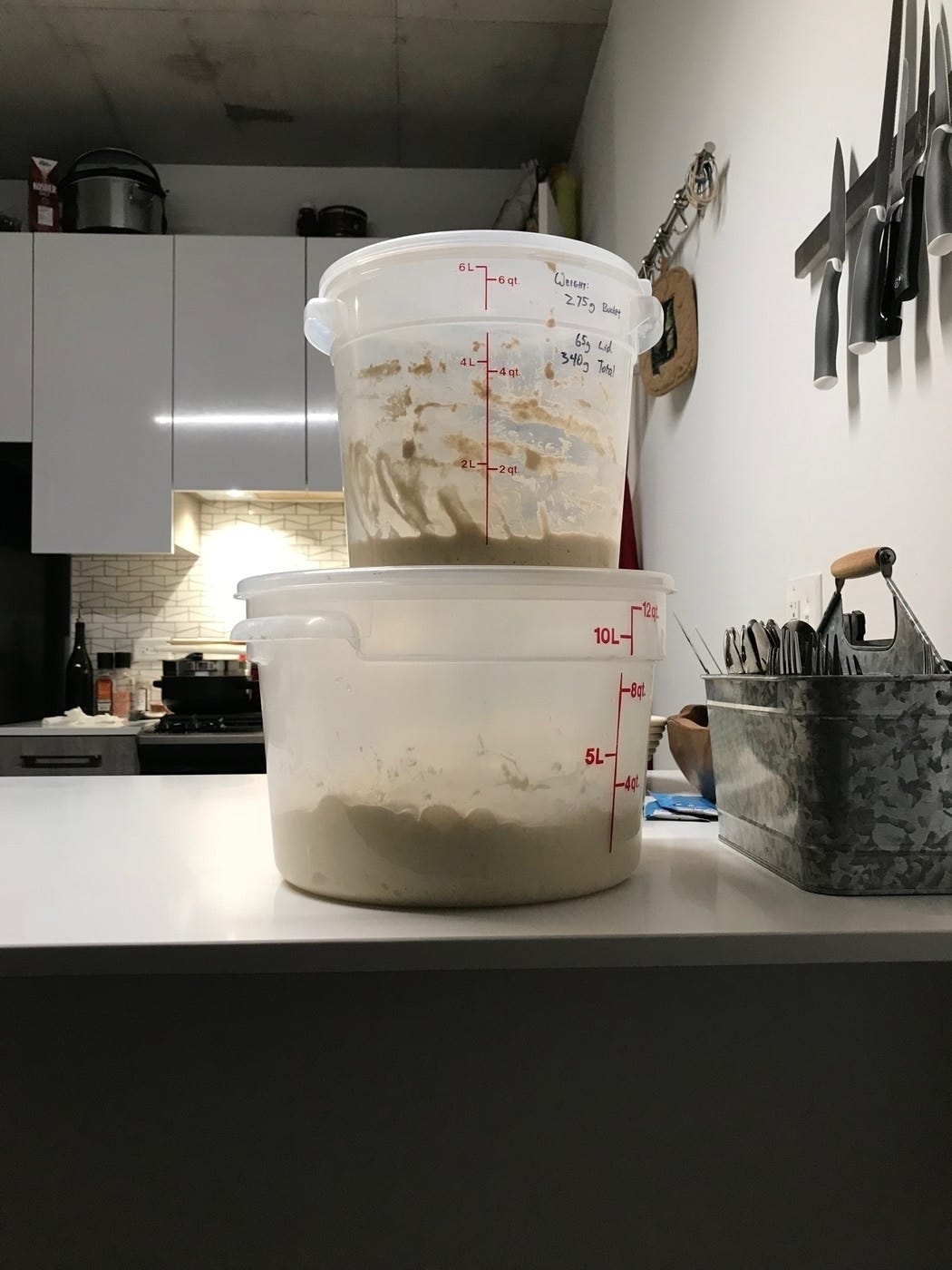

My first levain sourdough loaf. It’s the hybrid Pan de Campagne from from Ken Forkish’s book Flour Water Salt Yeast.

I started fermenting the sourdough culture on June 20th.

I mixed the first dough on June 25th.

That dough went into the oven in the morning of June 26th.

There was a tang of sourness, but it was light and airy. A great sandwich bread.

The next batch is coming tomorrow.

This is my favorite story about show business.

Glenn Miller’s orchestra, they were doing some gig somewhere, they can’t land where they’re supposed to land because it’s winter, a snowy night.

So they have to land in this field and walk to the gig.

And they’re dressed in their suits. They’re ready to play. They’re carrying their instruments. So they’re walking through the snow, and it’s wet and it’s slushy, and in the distance they see this little house.

And there’s lights on in the inside, and this billow of smoke coming out of the chimney. They go up to the house, and they look in the window, and in the window they see this — this family.

There’s a guy and his wife, and she’s beautiful. And there’s two kids. And they’re all sitting around the table. And they’re smiling, they’re laughing, they’re eating. And there’s a fire in the fireplace.

And these guys are standing in their suits, and they’re wet and they’re shivering and they’re holding their instruments. And they’re watching this incredible Normal Rockwell scene.

This one guy turns to the other guy and goes, “How do people live like that?”

“My son, my loyal and affectionate boy, some day it may be yours to know the pain, the unreasonable pain that comes over a man to know that between him and his boy, and his boy’s friends, an unseen but unassailable barrier has arisen, erected by no human agency; and to feel that while they may experience a vague respect and even curiosity to know what exists on your side of the barrier, you on your part would give all—wealth, position, influence, honor—to get back to theirs! All the world, clumsily or gracefully, is crawling over this barrier; but not one ever crawls back again!” A 1908 letter from John D. Swain to his son, a student at Yale.1

I think about this paragraph often.

As I turn 28, I think about how I’m now sitting at the top of the wall. I can see both sides, feeling like I can fall backwards or forwards.

And when I look forward, I see a courtyard. It’s a beautiful garden, with birds and benches and green ivy.

I see a courtyard because I now understand how much time is required to achieve the important things in life. You have to be consistent, every day, over a long period of time in order to cultivate happiness, and peace, and health.

Reading about the collapse of Europe ahead of World War II. Running every single morning. Choosing to prepare your own salad. Knowledge, health, and wellness.

These are the things that money can’t buy.

Only time can buy them.

And it’s what I imagine doing in my courtyard, every day, so that my garden becomes beautiful - slowly, and over time.

What does it mean? Where did it come from? Why have we all adopted it as a conversational tic?

Elizabeth texted me last week, “I’m sad we don’t have much more time here, there are so many things I want to do.”

A major benefit of leaving a city is it forces you to do the things you’ve been putting off until “some other day.”

When I left Nashville, I scrambled to go to a Titans game, to catch another Ryman show, to get beers with some mentors of mine.

Now we’re leaving Chicago. We can’t say these things anymore:

Now’s the time to see those friends, to eat at that restaurant, to throw that party.

There’s no sense in wasting time doing things you feel obligated to do if you’re leaving soon.

When I read the news, I accept everything as it’s written as fact. I soak up geopolitics and stock analysis, questioning nothing until I encounter an article about Net Neutrality. And then I shake my head, because the article is egregiously wrong. The article will lack nuance or, worse, will completely mix up the motivations of the subjects involved.

But then, after being exposed for the consensus-driven drivel it is, I’ll turn the page and go right back to taking every sentence I read at face value.

Michael Crichton called this the Gell-Mann Amnesia. “Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them. In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read.” 2

I think Crichton is right, but I don’t think it’s because we have short-term amnesia.

I think it’s because we don’t know what we know.

We all seem to have the tendency to think that whoever we’re talking to knows what we know. The reason we assume other people know what we know is because assuming the opposite - that other people don’t know what we know - is hard work.

For example, it’s hard for a computer scientist to describe a database to a kindergartner. It’s not that a database is a complicated concept, but instead it’s because we don’t know what a kindergartner’s reference point is. “Do they know what a garage is? How about a warehouse? Can I mention arrays?”

With kindergartners, it’s obvious they don’t know everything we know. But for people our age, and certainly for people who are paid to write Big And Fancy Articles, we assume they know at least what we know. If we didn’t assume that other people share our knowledge, then communicating would be an order of magnitude more difficult. We’d spend our whole day trying to explain databases to kindergartners.

Pop culture has termed this phenomenon “You don’t know what you know.”

There are at least two negative consequences of ignoring our unknown knowns.

The first is that we share our ideas less. If I read something, and have an insight, my first reaction is usually, “Everybody else has already thought of that.” The reality is few people come to the same conclusions as any of us do. Yet I struggle to write posts or mention ideas because I assume everybody else has already considered them.

The second negative consequence is intellectual envy. I get envious of people when they post interesting insights. When somebody Tweets something thought-provoking, I am in awe of the concept. I begin to feel intellectually inferior because I assume that 1) the author knows everything that I know, and 2) they’ve added a new and original thought on top of everything I already know.

We are so quick to discredit ourselves. We are quick to forget what we know. And because we don’t know what we know, then we assume everybody knows everything we know.3

It’s a small subtlety, but it inhibits us.

I am fascinated by Steven Pinker’s example of how humans remember things1.

Our brain can hold only about six bits of information in our working memory at once.

M D P H D R S V P C E O I H O PHow many of those letters can you remember immediately after reading them?

If we compress the random letters above into familiar groups, we’re able to remember them all easily:

MD PHD RSVP CEO IHOPIt’s easier to remember them all when they’re condensed into five chunks. But we can do even better:

The MD and the PhD RSVP'd to the CEO of IHOP.One chunk.

Stories are our competitive advantage as a species. The great storytellers among us can wield outsize power2.

“It never gets easier, you just get faster.”

There is something inspirational in knowing that Greg LeMond also sweats his face off when he bikes for an hour. The main difference between me and him is that when he bikes for an hour, he can ride the length of an entire marathon.

It reminds me of learning PHP late at night at a tiny desk on the 7th floor of Central Library. If my laptop wouldn’t spit out what I expected, I’d threaten to throw it out the window.

My laptop never listened to me.

I often forget about my late nights in Central Library. I forget how maddening it was learning how to program.

Nowadays I can easily store values in variables and manipulate strings. But figuring out the right system of tests to run or the right database architecture to choose is still maddening.

Learning is hard. I hope it keeps feeling hard.